Since the Enough Courtney campaign began, I’ve heard some defense of Senator Peter Courtney. More, frankly, than I expected. The most interesting comments so far have been in defense of the nepotism laws in Oregon that allow legislators like Courtney to hire and pay their family members. I’ve heard Oregonians say this is appropriate because we pay our legislators so poorly in Oregon, $24,216 per year plus per diem. It doesn’t amount to much.

Since the Enough Courtney campaign began, I’ve heard some defense of Senator Peter Courtney. More, frankly, than I expected. The most interesting comments so far have been in defense of the nepotism laws in Oregon that allow legislators like Courtney to hire and pay their family members. I’ve heard Oregonians say this is appropriate because we pay our legislators so poorly in Oregon, $24,216 per year plus per diem. It doesn’t amount to much.

But is this a good reason to maintain the lax nepotism laws in our state?

Why aren’t we paying our legislators for the important work they are supposed to be doing?

In California, a state legislator makes $104,118 plus per diem; in New York it is $79,500 plus per diem; and Washington is $47,778 plus per diem. Legislators in New York and California are considered full-time, but the position in Washington—like Oregon—is considered “hybrid,” which is supposed to mean, according to Ballotpedia, that “[legislators] devote about 74% of a full time job to their legislative duties.” Never mind the disparity between the legislative salaries of other “hybrid” states; there’s a bigger issue here.

Don’t we want full-time legislators in Oregon who can actually devote their time to understanding the complex issues facing our state, so they don’t have to pay their spouses to round out their salaries or work other jobs that take them away from truly understanding the problems in Oregon?

Not surprisingly, almost ALL Oregon legislators are either wealthy, retired, self-employed, or have a day job to supplement their “hybrid” position in Salem.

Peter Courtney is no different. On top of having his income supplemented by employing his wife, he also held a day job, working at Western Oregon University (WOU) for 30 years. As stated in the Western Edge Magazine of WOU, he worked as an assistant to six presidents, as an instructor of speech communication, and also as Commencement Committee Chair. He retired from this job in 2014.

From what I understand, he was making $113,000 a year in the job at WOU and now has a pension of $68,000. Not bad for a hybrid legislator who had to hire his wife to make ends meet.

How can someone run our Senate and hold the most important and powerful position in our legislature and also work a job that earns him more than $100,000 a year? How does one do both of those jobs well? Obviously, this hasn’t worked for Peter Courtney.

Case in point: National Popular Vote.

National Popular Vote is a simple concept that Peter Courtney has been unable to grasp after ten years of legislative attention in Salem. In these ten years, he has had countless hours to read the 1,000-page book about NPV, brush up on the articles of the U.S. Constitution, and listen to the wise voices of the League of Women Voters, Common Cause, and other supporting organizations. Yet, our Senate President—again, the most powerful person in our legislature and maybe even in our state–still says things like the NPV bill “would effectively give away Oregonians’ electoral proxy to voters in other states.” A statement so false that it illustrates his complete lack of understanding of what is a very simple concept.

One person, one vote.

All votes equal.

It is as simple as that.

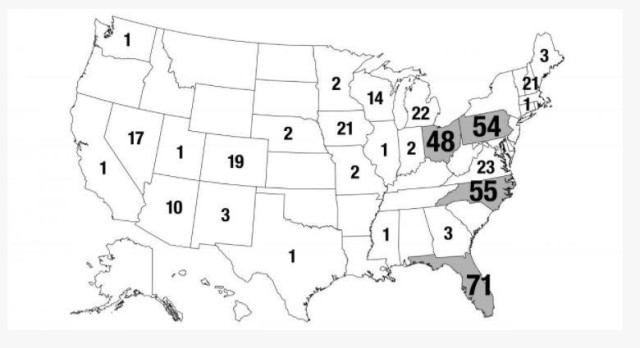

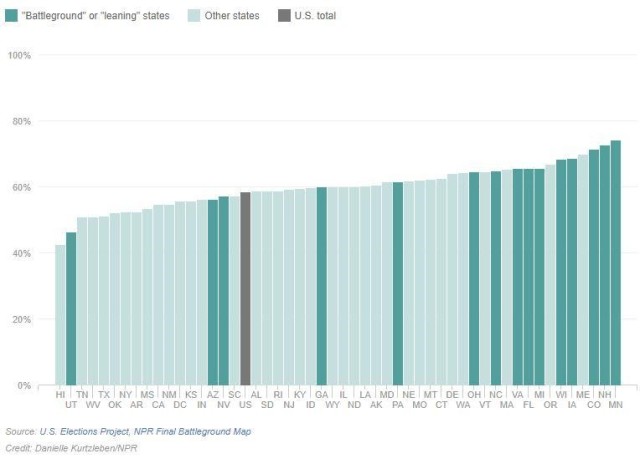

Maybe if Senator Courtney could just focus on one job and not worry about increasing his wages by hiring his wife or taking on extra work at a university, he would have the time to realize what is right for Oregon and what is right for our country. Maybe he would have time to understand that each vote in our country should be counted equally and that a vote in Florida shouldn’t hold more weight than one in Oregon.

Imagine our country if NPV were enacted.

There wouldn’t be spectator states and swing states. Presidential candidates would be forced to consider the issues throughout our nation and not focus unfairly on a select few. Our voter turn-out would rise. People would become more engaged in the political process. Voter suppression would drop and foreign meddling in elections would be a distant memory from the past. Our president would be someone elected by the people with every vote cast counting towards that election.

In Oregon, unfortunately, we are not going to get there without getting rid of Peter Courtney. We have an obstructionist Senate President who is spread so thin and is so ethically challenged that he can’t grasp the simple concept of NPV. But imagine if he could. Imagine if we really had legislators who worked full-time, who didn’t have conflicts of interests with other jobs, who were paid a decent, fair wage.

Imagine the possibilities.

I’ve come to accept that there are climate change deniers. I don’t agree with them, but I’ve accepted that they are out there and that they believe what they believe despite little credible scientific evidence to support their opinion that climate change does not exist or is not a threat.

I’ve come to accept that there are climate change deniers. I don’t agree with them, but I’ve accepted that they are out there and that they believe what they believe despite little credible scientific evidence to support their opinion that climate change does not exist or is not a threat.